The Ethiopians cultivated coffee from about the 8th century. The Iranian philosopher and physician Abu Bakr Muhammed ibn Zakariya al-Raz (Rhazes) first recorded the infusion about 900 AD. It appears to have been grown in Yemen from about 300 years later, the Red Sea port of Mocha becoming the exclusive entrepôt for its export. Following the conquest of Arabia by the Ottomans, coffee became established in the Ottoman Empire, spreading from there to Europe.

Demand…

In 1637, Nathaniel Canopus, a Greek scholar from Ottoman-occupied Cyprus, arrived at Oxford University, and became the first person to brew coffee in Britain—a decisive event which changed the course of Sri Lanka’s history. The British taste for the bitter beverage grew by leaps and bounds: adopted first by gentry and bourgeoisie, it trickled down to the large middle and working classes, created by Britain’s industrialisation. Between 1801 and 1841, according to The Overland Ceylon Observer and Monthly Précis of Ceylon Intelligence (15 November 1847), British coffee consumption rose from 1.09 oz (31 g) per head to 1 lb 13¾ oz (843 g). There was a huge and growing demand for the bitter bean.

… And Supply

In order to fill the rising need for coffee, enterprising Europeans used a mix of larceny and sex. Dutch merchants smuggled some plants out of Yemen about 1615, cultivating them in glasshouses in Holland, and establishing small-scale plantations in Sri Lanka and Java. A French marine, Captain Gabriel de Clieu, seduced one of the ladies of the court of the dilettante King of France, Louis XIV, obtaining through her a plant from the king’s herbarium (itself the offspring of gift from the Dutch). This he took to the West Indian island of Martinique, where he established a plantation. Using slave labour, coffee came to be grown throughout the West Indies.

Gabriel de Clieu smuggling a coffee plant to Martinique. Image courtesy Peter Baskerville

In 1727, the Brazilian diplomat, Francisco de Mello Palheta, by seducing the French Guiana governor’s wife, got his hands on some coffee beans, which he smuggled back to Brazil. These beans, with slave labour, made the Brazilian coffee industry the world’s largest.

Sri Lankan Experiments

When slavery ended in the West Indies in 1833, plantations elsewhere, with wage labour, became viable. Sri Lanka seemed a good enough place to cultivate coffee. Both Dutch and indigenous inhabitants had already planted the crop, the latter’s product being known as “native coffee”. However, they didn’t grow it on a large scale, and their management of the crop left a lot to be desired.

Early in the 19th century, according to Anthony Bertolacci, the British-held coastal areas of the island exported between 190 and 1,080 candies (48-274 tonnes) of coffee annually. He wrote:

“Its coffee is excellent, when it has not been gathered unripe, and when proper care is taken when drying it. But the ceylonese are inattentive in both… all birds are fond of it, particularly the crow; and of the latter there are such numbers… that the Ceylonese have great difficulty to protect their coffee from its destructive ravages, and are often induced to gather it before it arrives at perfection. Many of the natives injure the quality of their coffee by dipping it into boiling water before it is perfectly dry.”

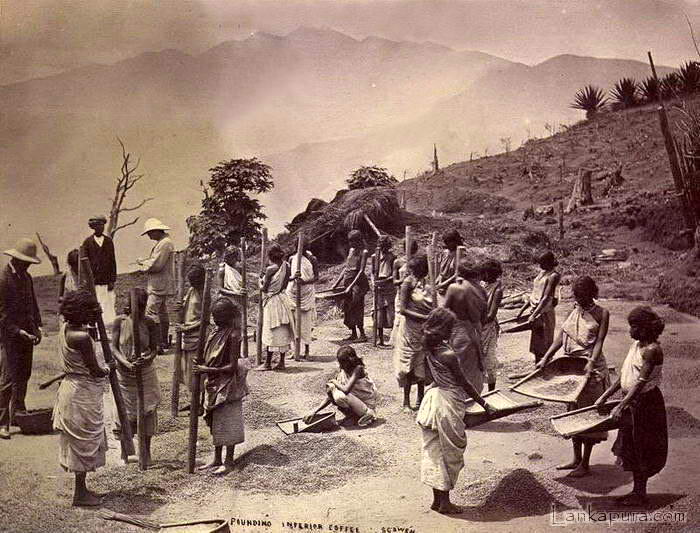

Pounding inferior coffee. Image courtesy Lankapura

George Bird established the first successful large-scale coffee plantation, near Kandy, in the 1820s, after being granted 80 hectares of land and a tax-free loan of 4,000 Rix Dollars by the colonial government, to do so. However, few people knew how to run coffee plantations. Most planters had never been in the tropics—according to one source, 95% of estate superintendents were Scots, half of them from Aberdeen, mostly recruited through informal networks. Almost all the coffee plantations set up before 1837, and quite a few thereafter, were failures.

Tytler’s Revolution

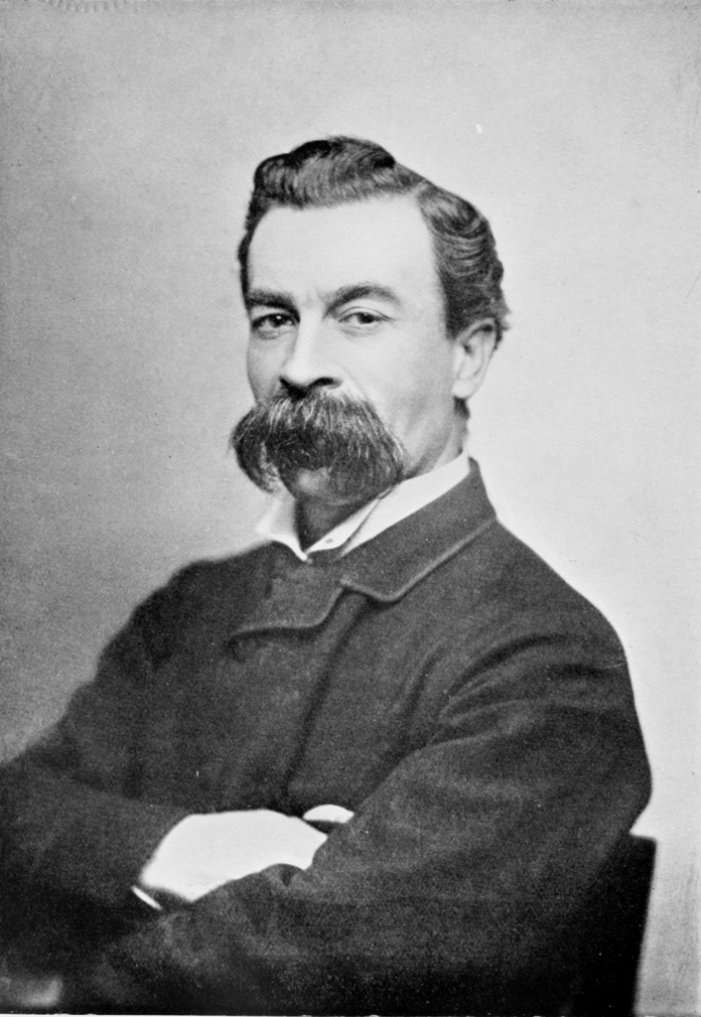

In 1837, the firm of Ackland, Boyd & Company employed yet another Scot, Robert Boyd Tytler—a relative of a partner, George Hay Boyd—to develop their coffee estates. Tytler, with experience of planting in Jamaica, came to be “regarded as the ‘father’ of Ceylon planters”, having introduced “the West India system of cultivation”, according to John Ferguson, in Ceylon in the Jubilee year.

Tytler brought with him a second-hand copy of Pierre-Joseph Laborie’s The Coffee Planter of Saint Domingo. Based on the author’s experience of the slave-labour methods of coffee cultivation used in Haiti, this book laid the foundations of Sri Lanka’s estate system, becoming the coffee planters’ Bible. Laborie’s techniques revolutionised the coffee plantations, regularising planting, manuring, pruning, and harvesting.

Robert Boyd Tytler, “The Father of Ceylon planting”, from the Tropical Agriculturalist.

Coolies

Coffee is seasonal, requiring large numbers of workers at harvest time to pick the ripe berries in time—over-ripe berries shrink and dry up. P.D. Millie, a veteran coffee planter, said in his Thirty Years Ago: Or Reminiscences of the Early Days of Coffee Planting in Ceylon, that Sinhalese peasants were well-built and suited to clearing the jungle for planting, a hard task. However, they weren’t so keen on working seasonally under draconian estate conditions. The violent punishments meted out on slaves in the West Indies continued to be used in this country until well into the 20th century. One former planter told this writer that the labour foreman, the Kangani, would tie a labourer to a tree and beat him with a stick.

Planters required itinerant workers, who were willing to labour under these conditions.

A solution came in 1839, when the colonial government reversed its opposition to importing South Indian labour. Millie thought the Tamil “coolies” were not suited to heavy work, but could perform adequately the repetitive tasks of coffee cultivation. William Sabonardiere, in The Coffee Planter of Ceylon, said: “Tamuls, particularly the women and girls, are far better pickers than Cinghalese…”

Very soon, tens of thousands of migrant Tamil workers streamed into the coffee plantations, altering permanently the ethnic make-up of Sri Lanka. According to Valentine Daniel, in his study of Estate Tamil culture, Charred Lullabies, they had very good relations with the Kandyan peasantry. This was not to last, however. Plunged into poverty, the Kandyans looked increasingly askance at the Tamil workers who, it seemed, occupied the lands they themselves once possessed.

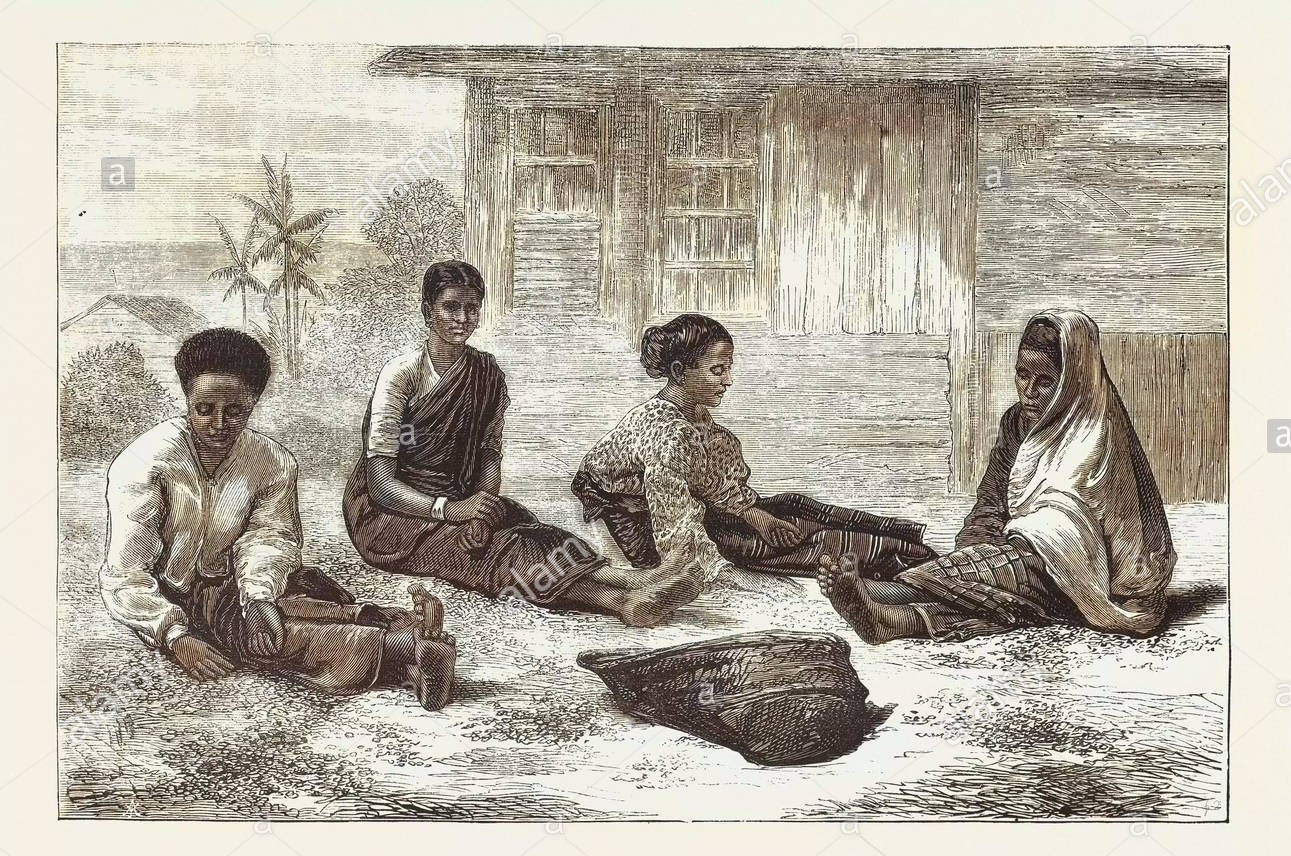

Estate workers, Dimbula area, photographed by Julia Margaret Cameron

Planter Raj

Now the planters needed land on which to grow coffee, which, according to Georgetown University’s Dr. Asoka Bandarage, the colonial government fulfilled by enacting the Crown Lands (Encroachment) Ordinance, expropriating thousands of acres of common and forest land from the peasantry. It then sold this land at 5 shillings an acre to would-be planters. She says that many of the buyers were government servants, including the Governor, Army Commander, Surveyor General and several judges.

Although halted later, this created an unhealthy nexus between planters and the colonial government, which came to be called the “Planter Raj”. It distorted the politics of Sri Lanka, even after the introduction of universal adult franchise. For example, Colombo was developed as a port instead of Galle—which lay closer to the East-West trade route—at twice the price, because the planters wanted it. The planters’ needs led to the frenetic construction of roads in the Upcountry, and later to the introduction of the railway between Colombo and Kandy.

Under the benign eye of the colonial government, a “Coffee Mania” began, similar to the “Gold Rushes” which took place in California and Australia shortly after. According to K. M. de Silva’s A History of Sri Lanka, investment amounting to GBP 5 million (LKR 80 billion in today’s currency) poured into coffee. By 1848, about 600 estates contained 50,000 acres (20,000 ha) of land. This acreage continued to grow.

This had a disastrous impact on the peasant economy. Hitherto, the Sinhalese farmers had used three tiers of agriculture: paddy lands at the bottom, home gardens above them, and the forests were left as a watershed, for collecting fruits, roots and herbs, and for slash-and-burn (chena or swidden) agriculture. While paddy was essentially for subsistence, with the surplus going as ground rent, chena-grown vegetables provided market produce. Deprived of forest land, the farmers fell back to subsistence agriculture. This caused the agrarian backwardness which has bedevilled Sri Lanka’s economy ever since.

Ecological Disaster

When coffee plantations encroached on the forests, they depleted the watersheds, causing the farmers to go uphill in search of paddy lands with water-access, also resulting in disastrous floods and landslides in place of a regular flow of water. To make the situation even worse, the effluent from coffee processing became a pollutant.

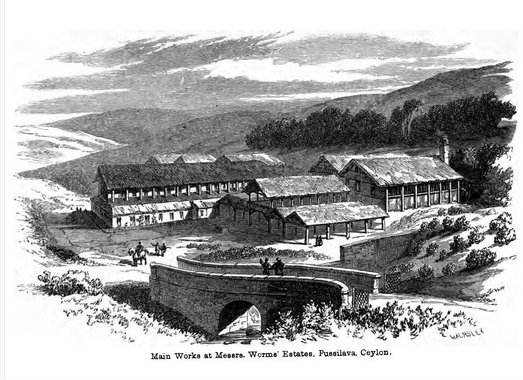

The works at Rothschild, Pussellawa, from William Sabonadière’s The Coffee Planter of Ceylon

The effect on wildlife was catastrophic. Previously, the dense forest cover provided an Upcountry habitat for a variety of animals. They were now driven from their homes. What happened to the Upcountry elephants provides a case in point. Probably 10,000 elephants lived on the island when the British arrived, but only 2,000 when they left. Until 1830, elephants were so numerous that the colonial government actually paid for them to be killed. In the space of a decade, 5,000 were eliminated in this way. However, the population might have recovered were it not for loss of habitat.

Chena cultivation is compatible with the presence of elephants. Before coffee, elephants roamed the hills at will: Moon Plains, Nuwara Eliya, used to be called “Elephant Plains”, and Horton Plains abounded in the pachyderms. Today, the only remnant of the vast elephant population of the Upcountry is just one herd of 15-20 elephants, living in the Adam’s Peak wilderness area.

High Tech

Apart from the danger from wild beasts, especially elephants, who killed several of them, the planters who flooded into Sri Lanka during the coffee rush had to face considerable hardship. In the absence of roads, getting to the land could be quite an adventure. Forests had to be felled, the coffee planted, and accommodation built for human and machine. The planter’s bungalow was just a rude log hut, his bed a chest or a plank with a blanket on it.

These conditions dictated that planters be of adventurous character. Being completely new to the field, they tended to be open-minded and innovative. They experimented with cultivation techniques, new forms of fertiliser, and new methods of processing—perhaps the most critical part of coffee production. Planters corresponded with leading European scientists, such as Justus von Liebig.

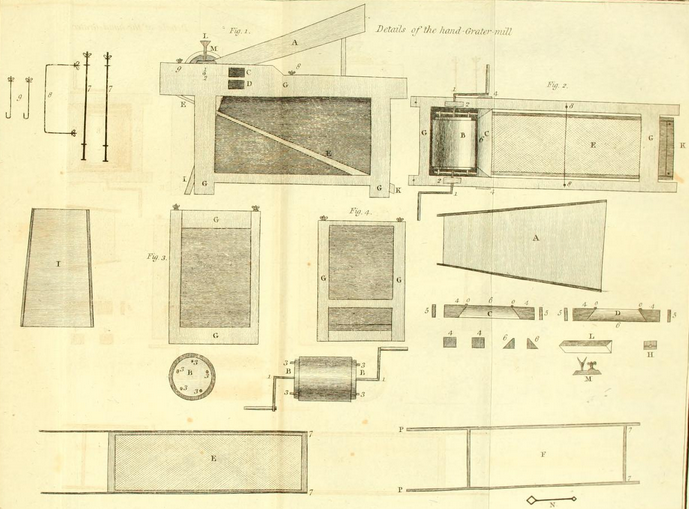

Laborie’s rattle trap; Caption: Wooden “rattle trap” pulper, from Laborie’s The Coffee Planter of Saint Domingo

Once plucked, the coffee berries began to ferment, so they needed drying. Removing the dried outer pulp could be difficult, so this had first to be done before drying, for which the planters used pulping machines. Originally, they used “rattle traps”, wooden pulpers, as described by Laborie, but soon switched to the water- or steam-driven steel machines designed by the Worms brothers’ engineer, A. Brown. The pulped beans, with only a thin “parchment” covering them, had then to be washed—removing any remaining pulp—and dried.

In the damp climate, it was not always possible to sun-dry the beans, so a young planter called Clerihew came up with a dryer, called a “Clerihew store”, the ancestor of modern tea and coffee dryers and heaters. Among developers of mid-19th-century high technology, John Walker stands out. He developed a vertical pulper and started manufacturing other coffee machinery. In 1854, he set up John Walker and Company, now Walkers CML, in Kandy, where his brother William joined him six years later. Not only did he supply the local market, but also exported to other coffee-manufacturing countries.

The dried beans had to be stored for long periods, after which they were transported down to Colombo for milling off the parchment and preparing for export. Transportation by bullock cart could be quite costly, and took a long time, so railways became a necessity.

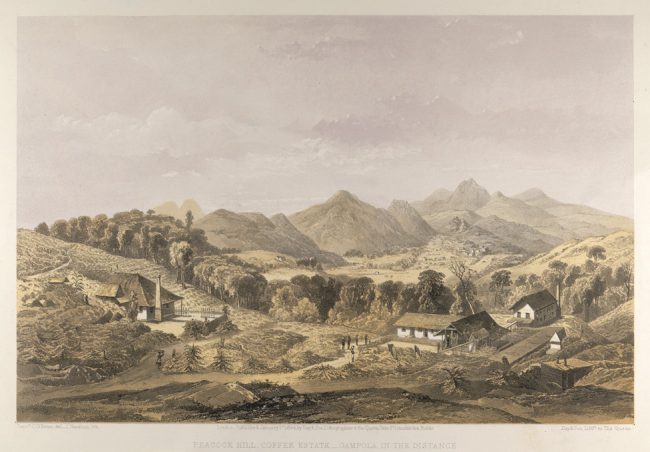

Peacock Hill coffee estate, Pussellawa, courtesy British Library. The building with a chimney at the right of the picture is a Clerihew store.

The Blight

A financial crash in Europe ended the Coffee Mania in 1848. Several firms went bankrupt, and many planters went to Australia, during the gold rushes. The ones who remained, however, became experts and made considerable fortunes.

Pushed by rising prices on the world market—according to K. M. de Silvas’s A History of Sri Lanka, the average in 1875-89 was about 109 shillings per hundredweight (about LKR 2,250 per kg today)—coffee production and exports increased by leaps and bounds. Plantation land totalling 110,565 hectares had been put under coffee by 1878. In 1868, coffee exports exceeded a million hundredweight (about 50,800 tonnes) for the first time; peaking at 53,600 tonnes in 1870.

Leaf infected by coffee rust, Hemeleia vastatrix. Image courtesy Wikipedia

Then disaster struck. In 1869, a hitherto unknown leaf disease broke out in Madulsima, whence it spread all over the coffee lands. The so-called “coffee rust”, identified as a fungus, Hemeleia Vastratix, devastated the coffee industry, earning it the name of “the Coffee Blight”. It later spread to every coffee-producing country, except Hawai’i.

The colonial government employed a British botanist, Harry Marshall Ward, to investigate the rust. He demonstrated that fungus spores were disseminated by the wind, and recommended growing trees between plantations to reduce this; and the avoidance of monoculture and planting different cultivars of coffee to limit the spread of the rust.

Harry Marshall Ward. Image courtesy Wikipedia

Some planters introduced more rust-resistant Robusta plants or hybrids, but it was too late. The planters had maximised returns by removing almost all vegetation apart from a single strain of Arabica coffee.

By 1917, only 330 hectares remained under plantation coffee in Sri Lanka. In 1920, the country imported 840 tonnes of coffee, while exporting just one tonne. Planters switched to cinchona, and then to tea. The Sinhala expression Kōpi Kāle (“The Coffee Era”) became a synonym for “very long ago”.

Modern Coffee Production

In the 1970s, the country began exporting coffee again, a process which accelerated with the nationalisation of plantations. This writer found that, on state-owned plantations, coffee was interplanted with tea, estate workers being allowed to harvest it on their own account, to boost their incomes.

Exports peaked at 5,268 tonnes in 1985, declining steadily thereafter, possibly due to lack of replanting following privatisation. So far, for the 21st century, coffee exports have remained well below the 1974 figure of 522 tonnes. In recent years, prices have risen to over three times the 1990 level but, while coffee yield has increased marginally, the area under cultivation has shrunk considerably. Coffee imports, once again, dwarf exports; the difference being that most of the imports are of coffee extracts (instant coffee).

Sri Lanka probably cannot compete against the huge Latin American coffee conglomerates which, paradoxically, modernised in reaction to outbreaks of the Coffee Blight in the mid-20th century, and supply the major part of the market, which is for instant coffee. Where Sri Lanka can compete is in the niche sector, for gourmet coffees. However, a concerted effort will be needed to regain the name which “Ceylon Coffee” once held.

Article copied – Roar Media